A study titled ‘Depression as a disease of modernity’ was published in 2012 source: (https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3330161/…) The findings, contrary to expectations, were alarming and compelled the authors to acknowledge that traditional/religious oriented societies seemed to fare better than modernized systems.

In my analysis of the study, I will examine the research’s authenticity, considering the topic’s sensitivity that might have influenced errors in previous findings. Furthermore, I will illustrate a discernable rise in depression within modern and modernizing societies, and then finally discuss the study’s conclusions and how they contradict the aspirations of those yearning for modernization.

Authenticating the Research

The study, authored by Dr. Brandon Hidaka at the University of Kansas, initially delves into the existing information on the topic before Dr. Hidaka’s own research. It was discovered that earlier studies, conducted a decade or more ago, often underestimated the rates of depression due to the ever-evolving perception of the mental illness.

Systematic epidemiologic study of depression began in the 20th century. Unfortunately, measurement of clinical populations (rather than community sampling), recall bias of retrospective studies, and inconsistent findings from longitudinal surveys bedevil this research.It was suggested this reflected the social trend to view emotional problems as treatable psychiatric conditions and not merely part of the normal vicissitudes of life

The misclassification of depression as an illness and changes in diagnostic criteria are frequently cited as reasons for the apparent rise in depression cases. However, Dr Hidaka’s review avoids this contention by “only assessing rates of depression as currently defined symptomatically.” Even to this day, the majority of diagnosed depression cases rely on confirming the prevalence of symptomatic behaviors, making the research, despite being a decade old, aligned with the latest trends. Other discrepancies in previous studies were also found to be erroneous as cases, or the lack thereof, were inaccurately reported, and investigators “attribute this discrepancy to methodological modifications implemented to reduce false positives.”

To eliminate the previously mentioned errors, Dr. Hidaka opted for longitudinal studies to avoid recall bias. Trends amongst US and Swedish populations, particularly its youth, showed a clear increase in the number of registered depression cases. The authors concluded that: “available evidence suggests we may indeed be in the midst of an epidemic of depression.”

The link between Modernity and Depression

Dr. Hidaka acknowledges mood disorders and loneliness as early markers of onset depression, often attributed to drug and alcohol abuse, which has become a hallmark of modern societies. The study recognized that depression’s prevalence is on the rise due to co-morbidity, as mood disorders are usually exhibited at the onset of depression. The lifestyle of the youth, with drug and alcohol use, emerged as clear outliers, significantly impacting an individual’s susceptibility to develop depression.

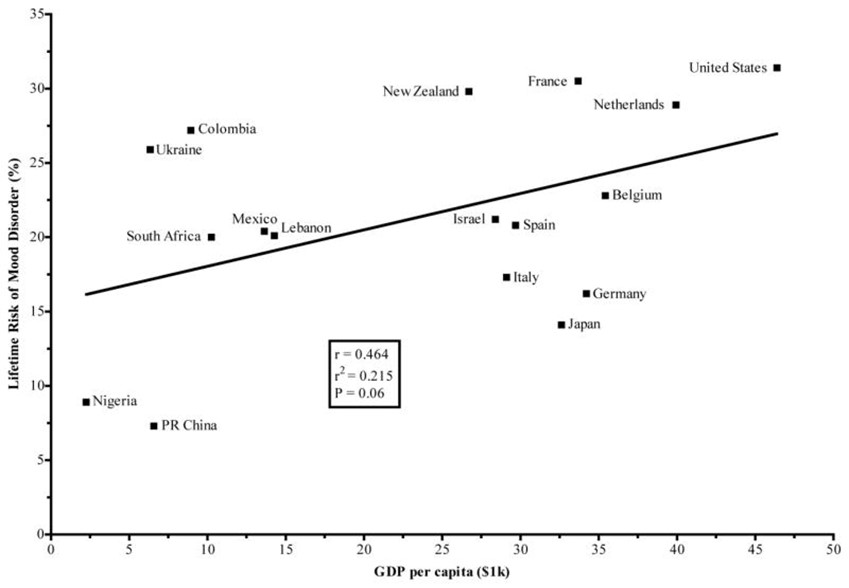

To further illustrate this connection, data was collected and presented correlating the lifetime risk of mood disorder (an onset indication of depression) with GDP, a quantitative measurement frequently used to gauge the modernization of a society (“Rethinking Islam and the West” 99). Trends demonstrated a statistically significant correlation, suggesting that as a society’s GDP increases, so does the risk of lifetime mood disorders amongst its inhabitants.

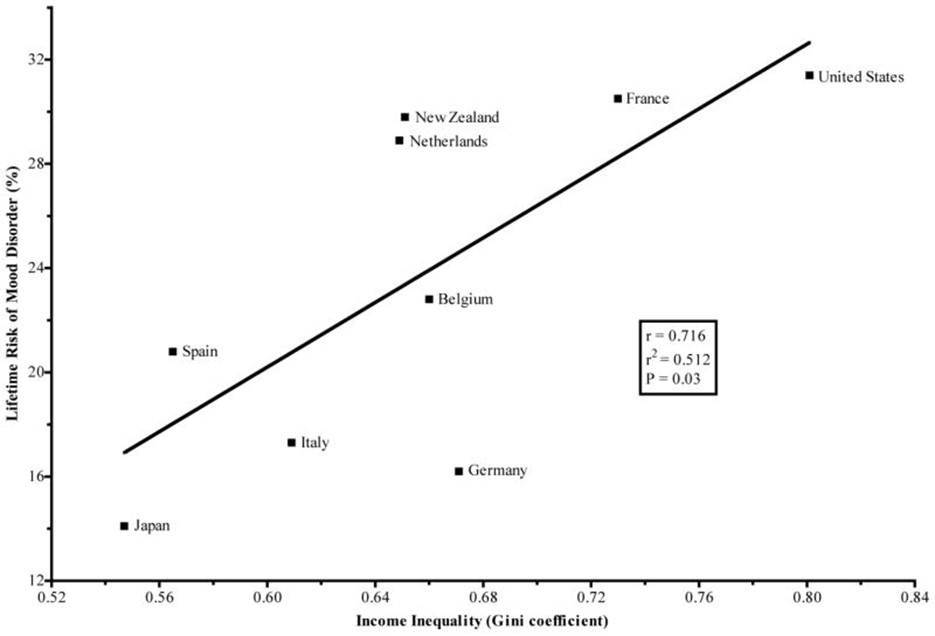

Countries that have historically championed modernization find themselves in a precarious situation. Their populations show the highest susceptibility to depression and mood disorders. What’s interesting is that the authors of the study noted Japan to be an exception as it “exhibits a relatively low degree of inequality for a highly modern, capitalistic society” because of its “cultural emphasis on collectivism, as opposed to individualism.” The study suggests that an excessive focus on economic and financial development, whether at the individual or societal level, leads to a higher incidence of depression. This realization may enlighten the reader, that in this context, capitalism and communism, despite being considered as two supposedly distinct economic ideologies, may not be as different as presumed.

The correlation between depression and modernity therefore suggests a notably low prevalence of depression in traditional societies. Examples include basic hunter-gatherer communities, “developing” nations, and well-known groups like the Amish. Evidence also showed that as traditionally oriented societies were exposed to modernism, their rates of depression, suicide, and obesity rose rapidly. For instance, when the indigenous circumpolar peoples were rapidly modernized “there was a rampant incidence of diabetes and suicide rates tripled within a decade.” Similarly, the transition of Ik people of Uganda from a hunter-gather lifestyle to the relatively modern agricultural practices reportedly led to a heightened sense of depression within their community

Indexing modernization by measures of various other common factors reveal that “the degree of modernization [..] correlate with a higher prevalence of depression in a dose-dependent manner.” And that the “adoption of the American lifestyle appears to explain higher rates of depression in Mexican Americans born in the U.S. compared to Mexican immigrants.”

As metropolitan China has undergone rapid cultural transformation over recent decades, the risk of suffering from depression appears to have risen dramatically: in a retrospective study, Chinese born after 1966 were calculated to be 22.4 times more likely to suffer from a depressive episode during their lifetime compared to those born earlier than 1937 (Lee et al., 2007). In developed countries, urban dwellers have a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders, and specifically mood and anxiety disorders, compared to rural counterparts (Peen et al., 2010). British households rated as more traditional, e.g. church-going, have lower rates of depression (Brown and Prudo, 1981). In an investigation of affective disorder prevalence among the Amish, a community that maintains a traditional agrarian culture with notable unity and social connectedness, the prevalence of MDD was found to equal that of bipolar disorder- about 1% (Egeland and Hostetter, 1983). The above evidence suggests higher depression prevalence and risk is associated with general aspects of modernization.

The authors recognize 5 major components of modernity that contribute to the rising rates of depression. 1. Obesity 2. Diet 3. Physical activity 4. Light and sleep 5. Social environment. It’s interesting to note that despite their findings, the authors seem unable to fully break away from a naturalistic worldview, such that every explanation and analysis is given within a non-transcendent framework.

Income inequality was also acknowledged as another contributing factor, which again can be attributed as a gift of economic and social principles born out of modernity. “Inequality has risen in modernized countries, and unequal societies tend to have lower overall health and higher levels of social distrust, competition, and status anxiety.”

Conclusions

“This trend toward isolation is alarming as loneliness appears to spread through social networks as a contagious process with a positive-feedback loop in which people with fewer friends become increasingly isolated and lonely over time.” As mentioned earlier, Japan seems to have saved itself from the rapid rise in depression by preserving communal values, something the Western societies have notably failed to do. The atomization resulting from material comforts and disenchantment from higher values leads to an intensifying cycle of depression as individuals seek more comfort to fill the void created.

“A move toward secularization of modern populations should also be considered, as religious activity is correlated with lower risk of depression and more social support”. Dr. Hidaka cited a separate study in search of the correlation between lower rates of depression and societal values. Religious values stood out to be a constant outlier, the study he cited quotes exactly “The teachings of Freud and others during the early twentieth century concerning the neurotic influences of religion have had an enormous impact on the field, nullifying the quite favorable views toward religion held by nineteenth century psychiatrists.” Religious values show resilience against societal development, retaining their significance, whereas modernity however establishes itself but also strips society of any transcendental values. Leaving no room for escape.

Technology may be contributing to an increased risk of depression in a variety of ways. Internet use has been correlated with less family communication, smaller social circles, more depressive symptoms and greater feelings of loneliness

“In conclusion, the modern social environment is more competitive, inequitable, and lonely. This deterioration of social cohesion among modern-industrialized populations may be a central component to rising rates of depression.” Something Mostafa Badawi emphasizes in his book as well: “A disordered society without any higher principles other than the explicit aim to satisfy as many of its members’ physical appetites as possible cannot control deviant tendencies. It has no option but to legitimize them. Identity crises are a product of the modern world. In a traditional environment where everyone knows his rights and his duties, where roles are well defined, and where the notion of an afterlife still exercises some influence, such crises need never arise” (Badawi, 77)

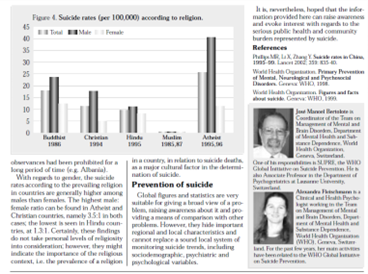

“Greater competition, inequality, and loneliness are the principal factors of the modern, western social environment blamed for rising rates of psychopathology, including depression”. This conclusion circles back to the initial point, emphasizing that modern society strips and replaces religious values in the public sphere with aggressive economic and welfare measures, leading to the destruction of communal sentiments Despite this, closely-knit societies such as Muslim societies still outperform others due to their continuous emphasis on maintaining family ties, participation in mosques, and supporting of the needy. This is evidently in the observation of suicide rates amongst various religious groups. The reader should note the values of the group with the highest rate.

Put another way, the modern man would likely be much more resilient to the toils of living if he were physically fit, well-rested, free of chronic disease and financial stress, surrounded by close family and friends, and felt pride in his meaningful work.

“More money does not lead to more happiness. By appealing to evolutionary proclivities, like a desire for energy-dense food and status competition, the economic and marketing forces of modern society have engineered an environment promoting decisions that maximize consumption at the long-term cost of well-being. In effect, humans have dragged a body with a long hominid history into an overfed, malnourished, sedentary, sunlight-deficient, sleep-deprived, competitive, inequitable, and socially-isolating environment with dire consequences. Hopefully, this theoretical framework will aid in the understanding, prevention, and treatment of depression and other diseases of modernity at the clinical and population level.” No quote best captures the entirety of what is stated here and the conclusion of this study other than Ahmed Keeling’s noteworthy analysis, in his book “Rethinking Islam and the West”: “Modern man is trapped in a system that is failing. Unable to see beyond the walls that imprison him, he clings on in the vain hope that somehow the multiplying crises will be solved by the very science and technology that is causing the destruction in the first place.”

- Hidaka B. H. (2012). Depression as a disease of modernity: explanations for increasing prevalence. Journal of affective disorders, 140(3), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.036

- Religion and Mental Health: Evidence for an Association, www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09540260124661. Accessed 18 July 2023.

- Al-Badawi, M. (1999). Man and the Universe. Claritas Books.

- Keeler, A. P. (2019). Rethinking Islam & the West: A New Narrative for the Age of Crises. Equilibra Press.