This essay was originally written in Arabic by Dr. Muhammad al-Mukhtar al-Shanqiti, a Professor of International Affairs at Qatar University, for Al Jazeera. It was translated into English using AI and subsequently reviewed by human editors. The original Arabic essay, titled “The Impossible Secular State,” can be found here.

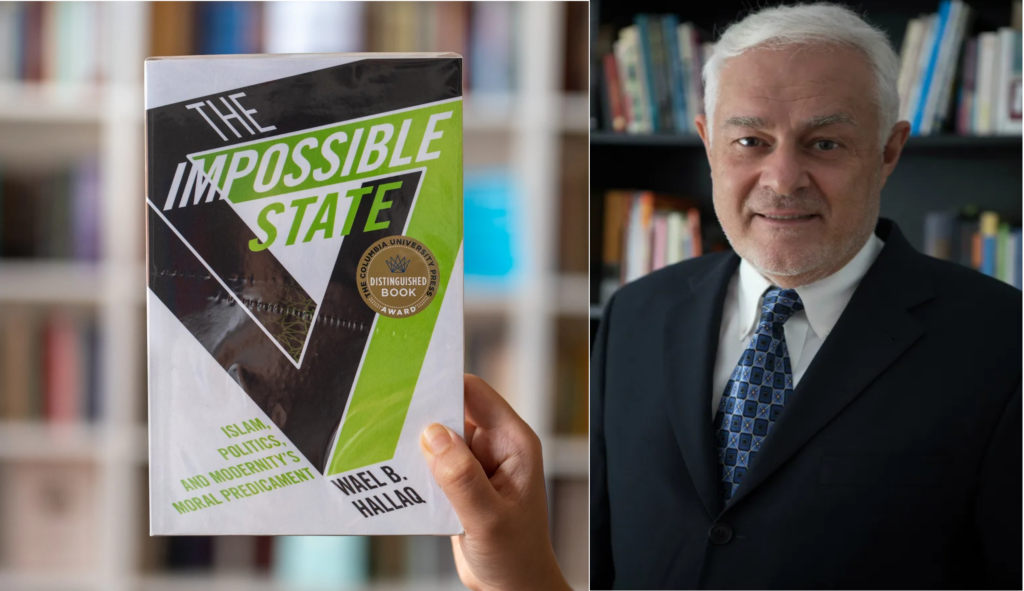

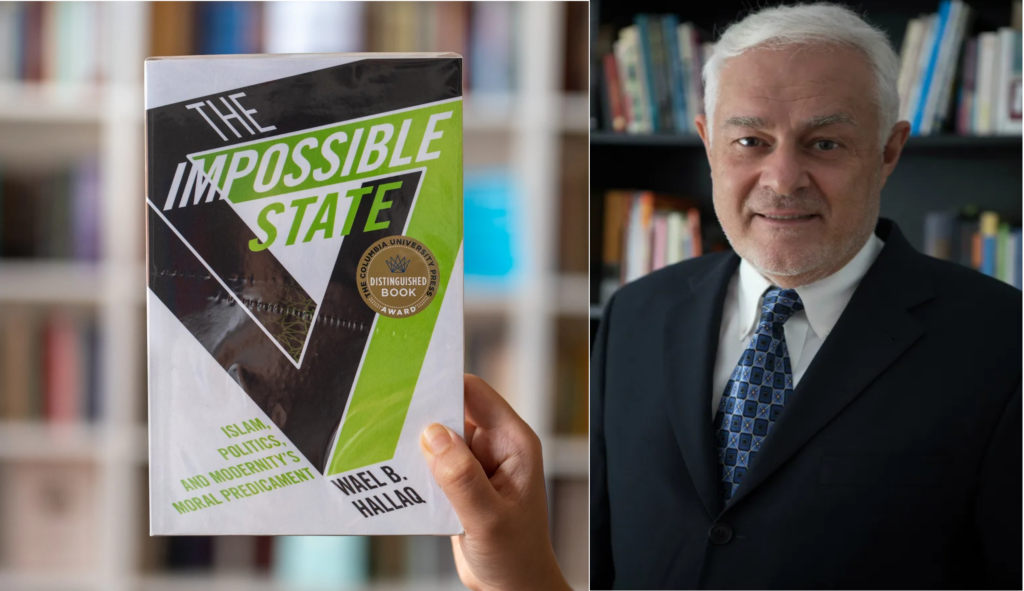

I could not find a more eloquent description of my feeling while reading Wael Hallaq’s book “The Impossible State” than the one John Locke used to describe his own feeling while reading his contemporary Robert Filmer’s (1589–1653) treatise on ‘Patriarchal Authority’, The Patriarcha.

John Locke says: “And truly I should have taken Sir Robert Filmer’s Patriarcha, as any other treatise,… had not the gravity of the title and epistle, the picture in the front of the book, and the applause that followed it, required me to believe that the author and publisher were both in earnest. I therefore took it into my hands with all the expectation, and read it through with all the attention due to a treatise that made such a noise at its coming abroad; and cannot but confess myself mightily surprised that in a book, which was to provide chains for all mankind, I should find nothing but a web of spider threads; useful perhaps to such whose skill and business it is to wise a dust, and would blind the people, the better to mislead them; but in truth not of any force to draw those into bondage who have their eyes open, and so much sense about them, as to consider that chains are but an ill wearing, how much care soever hath been taken to file and polish them.”

(John Locke, Two Treatises of Government, p. 5)

First: Between “Patriarchal Authority” and “The Impossible State”:

The similarities between the book Patriarchal Authority and The Impossible State are numerous. These include: the initial attraction to read the book due to the commotion surrounding it; the disappointment upon reading it due to its weak logical structure; the presence of a “group” seeking to promote the book, driven by political motives and religious or ideological biases. The only difference lies in the type of chains that Filmer and the group behind him sought to bind people with—namely, the authority of coercive monarchy claiming divine rather than popular legitimacy—versus the ideological defeatism through which Wael Hallaq and the group supporting him seek to bind Muslims, preventing them from drawing inspiration from their own values in the liberation struggle they are engaged in today.

Wael Hallaq defines the central thesis of his book by stating that “the concept of the Islamic state is impossible to realize and involves an internal contradiction, according to any prevailing definition of the modern state.” (The Impossible State, p. 19). He then softened the thesis somewhat—while also rendering it more ambiguous and contradictory—in a footnote on page 23 of the book. Regardless of Hallaq’s accuracy in diagnosing the phenomenon of the modern state, what is worse, in our view, is his understanding of the Islamic state. He does not define the Islamic state based on any normative vision derived from Islamic revelation or even Islamic political theory. Rather, he sees it embodied in “the theoretical-philosophical, social, anthropological, legal, political, and economic phenomena that emerged in Islamic history.” (The Impossible State, p. 38)

One of the strange aspects of Hallaq’s approach is that he focuses on Sharia in its moral, legal, and social dimensions, while completely ignoring the core Islamic political and constitutional values explicitly stated in the Qur’an and Sunnah—values that are essential for anyone engaging with the subject of the Islamic state. He even overlooks the rich legacy of Muslim political thought, referring only superficially to four books from that tradition! Moreover, the fundamental distinction between Islamic political values and Muslim political history is something Hallaq pays no attention to, and this was the starting point of a foundational flaw in his methodological approach.

Hallaq becomes captivated by the historical image in his conception of the Islamic state, in a strange convergence between a secular Christian intellectual and the activists of jihadist Salafism at its worst—marked by naivety and narrow-mindedness. The Islamic state that Hallaq claims to be impossible is no different from the imagined historical caliphate declared by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who appointed himself as its caliph. It is far removed from the Islamic state that today’s democratic Islamic movements are striving to build—movements that are far more significant and present than the chaotic Salafi groups that remain captive to a rigid historical model.

What’s ironic is that Hallaq—through this defeatist lens—criticizes the modern state in the tone of a Salafist Muslim, who sees popular sovereignty as the antithesis of God’s rule, and then criticizes the Islamic state in the language of a secular Christian, who sees no political role for religion. And yet, he fails to see that he has fallen into a blatant contradiction! Hallaq gathers together all the criticisms that Western thinkers have directed at the West itself and compiles them into a sweeping judgment about the failure of Western modernity. This is unfair to the Western experience, as it amounts to judging it by its margins rather than by its essence—like evaluating a medicine solely by its side effects, not by its healing power. Furthermore, Hallaq constructs an image of the Islamic state drawn from two flawed sources: the trajectory of Islamic political history, which often diverged from the values of divine revelation, and the fringe Salafi fantasies found in today’s Islamic culture. He then issues a sweeping verdict that the Islamic state is impossible. This is a profound injustice to Islamic political values, because what gives those values their normative meaning is the revealed texts, not the memory of history.

It is enough to illustrate Hallaq’s captivity to history that he uncritically accepts the binary of “Dar al-Islam” and “Dar al-Harb” mentioned in classical fiqh texts (The Impossible State, p. 105), treating it as an Islamic principle of international relations—despite the fact that this binary has no basis in the revealed Islamic texts and is merely a product of Islamic imperial history. Moreover, the contradiction that Hallaq identifies between the modern state and the premodern Islamic state equally applies to the contradiction between the modern state and premodern Christian, Chinese, or Indian states. Hallaq need not have resorted to the superficial argument that reproducing Islamic history—or any history—is impossible in the present age. No one disputes this to begin with. Do we really need a respected academic to convince us that imperial history—whether Islamic or non-Islamic—is no longer replicable today?

Hallaq has also argued that the localized nature of the modern state makes it incompatible with the concept of the Islamic state—which he envisions solely as a borderless empire akin to the model of “the Islamic State” (ISIS). Based on this, he concludes that it is “impossible for a nation-state to emerge based on the Islamic system of divine sovereignty.” (The Impossible State, p. 71). However, anyone with a basic understanding of the political values explicitly stated in Islam can easily recognize that these values are flexible enough to encompass the modern territorial nation-state, just as they once encompassed the world of empires. In fact, in both the textual language of revelation and the prophetic city-state model, the Islamic political vision is closer to the framework of the modern territorial nation-state than it is to military empires.

The truth is that Wael Hallaq’s thesis is a defeatist one—unjust to both the Islamic state and the modern state alike. It rests on a series of assumptions and stubborn claims without persuasive evidence. In essence, his conclusion is that the modern Western state is a failure, the Islamic state is impossible, and that, in fact, history has never known states at all. His defeatism goes so far as to claim: “There has never been an Islamic state; the state is a modern phenomenon.” (The Impossible State, p. 105).

The question that naturally arises here is: if “the state is a modern phenomenon,” does this mean that human history never knew the state at all prior to the modern era? Such a claim is nothing more than a sweeping assumption and obstinate denial of history. And if this is where Hallaq’s defeatist theory ultimately leads, then what distinguishes the Islamic state from other states—whether in its historical existence or its future possibility? Why is the Islamic state deemed impossible, while other forms of states—allegedly also non-existent in the past—are not? In the end, it becomes clear that this is simply a biased stance toward Islamic political values, and toward Islam itself as a religion—but one that hides behind convoluted language and a web of self-contradictions.

This defeatist approach offers no solution—neither to the crisis of Islamic civilization nor to that of Western modernity. Contrary to Hallaq’s defeatist stance and his portrayal of an eternal antagonism between Islam and the modern state, we believe that convergence between Islam and political modernity is not only possible—it is inevitable. But this convergence must be grounded in a solid normative foundation rooted in Islamic political values, not in aesthetic or circumstantial compromises, nor in nostalgic repetition of a bygone history. We also hold that the fate of Islamic civilization today—and perhaps that of human civilization as a whole—hinges on holding fast to the “betrayed” Islamic political values (if we may borrow Trotsky’s phrase from The Betrayed Revolution), not on abandoning or ignoring them. Muslim awareness of this truth is growing day by day—and this is unsurprising for anyone who understands the depth of the Islamic political textual tradition and the inspirational power of the early Islamic experience, particularly during the Prophetic state and the Rightly Guided Caliphate.

Wael Hallaq and the group celebrating his book may succeed in misleading some Arab youth and semi-educated Muslims—those who lack a clear understanding of Islamic political values, both in their normative scriptural form and in their complex historical development, and who are unaware of the dimensions of the current civilizational struggle over the heart of Islam. Such readers may be led to wager on yet another illusion. Nevertheless, the chronic political crisis in Muslim societies cannot be resolved by bypassing Islamic political values in favor of a secular system detached from the social and cultural foundations of these societies. The secular state is impossible to realize in the Islamic world except through coercion and force—and political coercion has no future in an age of popular revolutions and mass uprisings.

The Book and Its Author: Background and Trajectory

It seems to me that many of those who have engaged with Wael Hallaq’s book The Impossible State: Islam, Politics, and Modernity’s Moral Predicament in the Arab world lack sufficient familiarity with the author’s academic background and argumentative method. Therefore, before delving into specific points from the book in upcoming installments, we will first place both the book and its author within their proper context. Two aspects of Hallaq’s background are particularly noteworthy: First, his limited grasp of the Islamic political tradition; and second, his evasive style of argumentation—especially when discussing Islam’s present reality and its future prospects.

As for Wael Hallaq’s limited familiarity with Islamic political texts and the broader Islamic political tradition, this is evident to anyone who has followed his academic career and reviewed his scholarly output over the years. Unfortunately, this is something unknown to many of the young Arab enthusiasts celebrating his book today—many of whom have read nothing by Hallaq except The Impossible State, surrounded as it is by much noise and promotional fanfare about “the professor at the prestigious McGill University in Canada.” As for those who use the book as a propaganda tool—either against their political rivals from Islamic movements, or as an ideological weapon against Islam itself as a religion—they are not concerned with whether young Arabs understand much about the book’s author in the first place.

Despite Wael Hallaq’s extensive work in the history of fiqh and Usul al-Fiqh (Islamic legal theory), he has written virtually nothing of significance on Islamic political jurisprudence (fiqh siyāsī), and his many books do not demonstrate any serious engagement with Islamic political thought that would qualify him to venture a theory such as The Impossible State. The only exception is an article he published over thirty-three years ago, titled: “Caliphs, Jurists, and the Seljuks in al-Juwayni’s Political Thought” (Issue 74 of The Muslim World, published in 1984). However, this article is no more than a simple summary of some of al-Juwayni’s views, with contextual notes on his era, based primarily on secondary sources, such as the works of Orientalists like Rosenthal, Lambton, and Hamilton Gibb.

The book The Impossible State stands as a striking reflection of Hallaq’s meager grasp and limited engagement with Islamic political texts and the Islamic political tradition. This book, filled with sweeping generalizations about the political phenomenon in Islam and the political future of Muslim societies, does not refer to the normative political texts considered authoritative by Muslims—namely, the Qur’an and the Sunnah. Nor does it offer any serious survey of Islamic political history, which is rich with experience and lessons. Hallaq also fails to consult the foundational works of Islamic political thought, which number in the hundreds.

From the vast corpus of Islamic political heritage, The Impossible State cites only four works—those of Ibn al-Tuqtaqī, al-Māwardī, al-Ṭurṭūshī, and al-Maqrīzī. Meanwhile, the book’s footnotes are filled with references to branches of fiqh that have little to do with questions of state and governance. This reveals Hallaq’s limited command of the Islamic political tradition and his narrow perspective, confined largely to the jurisprudence of secondary legal rulings (fiqh al-furūʿ). Such a lens is insufficient for constructing a coherent vision of the political dimension in Islam—let alone for making bold claims and sweeping generalizations in this domain. Indeed, some of the passages in The Impossible State are merely reformulations of Hallaq’s earlier legal opinions, now transposed from their original legal context into a political one.

I believe that Hallaq has done a disservice to himself and to his own scholarly legacy—including the theoretical contributions he has made in the fields of the history of fiqh and legal theory—by venturing into a field in which he lacks expertise. In doing so, he appears to be trying to score ideological points in the ongoing global debate about Islam and politics, particularly in the wake of the Arab Spring uprisings and the intensifying Islamist–secularist polarization in Arab societies.

Whatever reservations one may have about Hallaq’s writings on fiqh and legal theory, they are far superior and more coherent than the ideas he presents on political values and political thought in “The Impossible State”. In this book, Hallaq addresses the question of the state from the perspective of juridical branches of law (fiqh al-furūʿ) rather than from the perspective of Islamic political jurisprudence (fiqh siyāsī). This approach led him into numerous theoretical entanglements for which he offers no solutions, and into sweeping claims he lacks the scholarly competence to substantiate. As the saying goes: whoever ventures into what he does not master brings forth absurdities.

The second point that a reader of The Impossible State should be aware of—and approach with discernment and wisdom—is Wael Hallaq’s evasive style of argumentation, especially when discussing Islam’s present and future. In his critique of Orientalists, Hallaq once wrote: “One of the essential conditions for the persuasive effectiveness of any discourse is that the motives behind the discourse not be clear to the reader or listener.” (*Hallaq, The Origins and Evolution of Islamic Law, p. 13) I know of no writer who has applied this intellectually questionable tactic—of obscuring his real motives in order to persuade Muslim readers of his views on the Islamic state and Islamic law—more than Hallaq himself.

The political, ideological—and even religious—goals that Hallaq pursues are always cloaked in ambiguous language and argumentation that winds through dark, twisting paths. He exaggerates his praise of the Muslim past as a prelude to draining all hope for their future. He stirs emotions by speaking of the superiority of Islamic law and the Islamic state over the course of twelve centuries before modernity—only to conclude that there is no hope of building anything resembling this Sharia or Islamic state in the future! He rebuts the Orientalists’ claim that the Prophetic traditions (hadith) found in the sound collections were fabricated—only to end up adopting their position, asserting that this view is no different from that of Muslim scholars, who regard solitary (ahad) hadith as probabilistic (not definitive) in nature!

The book The Impossible State is itself sufficient evidence of this twisted method. Instead of honestly presenting his views to Muslims about Islam as a religion with a political nature—either by accepting that, in line with the belief of the majority of Muslims, or rejecting it outright, as many secularists do—Hallaq takes a convoluted path to tell them that the Islamic state is impossible. But not because of Islam as a religion, nor because of the Islamic state in itself—rather, because of “modernity”. Even though the Sharia surpasses all forms of modernity, that, he claims, is a thing of the past—so don’t even think about it in the present or the future! Likewise, in his extensive work Shari‘a: Theory, Practice, Transformations—and in other books—Hallaq circles around only to conclude that Sharia cannot be codified, and is unfit to serve as law in the modern state. He attacks anyone who has attempted—or is attempting—such codification, including some of the great Muslim reformers of the 20th century, all after filling the book with glowing praise of the Sharia in the bygone centuries.

The summary of the book The Impossible State, and before it Shari‘a: Theory, Practice, Transformations, is this: an artificial praise of the Islamic past, and a firm despair regarding the Islamic future. This serves two purposes:

First: To sedate the Muslim reader by speaking of the glories of the past—especially if the reader is psychologically and intellectually vulnerable, delights in rebutting Orientalists, and seeks to “overcome his inferiority complex with an injection of pride to soothe himself,” as Malik Bennabi put it (The Orientalist Legacy and Its Impact on Modern Islamic Thought, p. 11).

Second: To use this sedative as a means of convincing Muslim readers to despair of any solution to their crisis that draws inspiration from Islam’s political values and legal teachings.

The Tunisian philosopher Abu Yaareb al-Marzouqi was among the first to recognize the dangers of this “sedative” in Wael Hallaq’s writings. He pointed out that Hallaq “adorned his thesis by flattering Islamic pride, glorifying the past, and claiming it was in the best possible state. Moreover, he highlighted its moral virtues, which he asserts are absent in the modern age, compared to what he claims were virtues of Islam— though he argues they no longer suit our times.” (Al-Marzouqi: “Is it true that the Islamic state has no future? Is it really impossible?”)

Two of the most astute critics of Wael Hallaq and leading scholars in Islamic law—Professors Mohammad Fadel and Emon Anwar of the University of Toronto—have also noted the tone of discouragement that pervades Hallaq’s writings on Islam whenever he addresses issues of the present and future. So, is the recurring theme of demoralization, conveyed in a subtle and roundabout manner in Hallaq’s discourse on Islam’s present and future, merely a coincidence? Or is it part of those “essential conditions for persuasive effectiveness” that Hallaq masters so well—and which many naive Arab youth are unaware of?

Third: Between Western Inability and Arab Inability

The Christian mind—in both its Western and Arab manifestations—still struggles to comprehend the fusion of the religious and the civil in the Islamic text and their integration in the foundational Islamic experience. What is truly surprising is that some Arab thinkers, even in the 21st century, remain unable to grasp the dual nature of Islam, composed of both the religious and the civil, despite the fact that some Western thinkers had already recognized this since the 18th and 19th centuries, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Gustave Le Bon. Rousseau, for instance, criticized the division between the religious and the civil in Christian history, and noted that Islam overcame this dilemma, which is rooted in Christian tradition. He wrote: “This dual authority led to a perpetual conflict of jurisdiction, which made it impossible for any sound political system to arise in Christian nations. People never truly knew whether they ought to obey the prince or the priest… For the spirit of Christianity swept everything away, and religious rites always remained independent of the sovereign—or rather, returned to being independent as they once were—with no organic connection to the body of the state. As for Muhammad, he had a very sound understanding. He tightened the bonds of his political system, and as long as the form of governance he established endured under the Rightly Guided Caliphs, that system remained unified and consistent. For that very reason, it was a sound form of governance.” (Rousseau, The Social Contract, p. 241)

As for Gustave Le Bon, he expressed his astonishment with a rhetorical question: “How can Islam cease to be the religion of the state in a land where civil law and religious law are united, and where the national identity is founded upon faith in the Qur’an? That is difficult to dismantle.” (Le Bon, The Spirit of Revolutions, p. 42) Perhaps one of the most eloquent expressions of this beautiful Islamic synthesis—and the Christian mind’s inability to comprehend it—was by Alija Izetbegović, who wrote: “Islam is the repetition of man. It has, just as man, its “divine spark,” but it is also a teaching of shadows and the prose of life. It has certain aspects which the poets and the romantics might not like. The Qur’aan is a realistic, almost antiheroic book. Without man to apply it, Islam is incomprehensible and would not even exist in the true sense of the word. Christianity was unable to accept the idea of a perfect man who was still a man. Muhammad, however, had to remain just a man. Muhammadﷺ gave the impression of a man and a warrior, Jesusعليه السلام gave the impression of an angel.” (Izetbegović, Islam Between East and West, pp. 194–195)

Wael Hallaq, in his book The Impossible State, appears to be—consciously or unconsciously—captive to his Christian intellectual background. This has led him to internalize a number of implicit assumptions about the relationship between religion and the state, assumptions which have no connection—either in letter or spirit—to Islam, but rather reflect the Christian perspective on that relationship. Hallaq’s opening statement in his book— “The concept of the Islamic state is impossible to realize and inherently contradictory” (The Impossible State, p. 19)— is almost a literal replication of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s famous assertion: “I am mistaken in speaking of a Christian republic; the two words are mutually exclusive.” (The Social Contract, p. 247)

As for the Arab context, Wael Hallaq was not an innovator, but rather a follower. The Christian roots of Arab secularism are not a new phenomenon; in fact, more than one scholar has observed this long ago. Among these scholars is Hassan Hanafi, who wrote: “Secularists in our region—since the time of Shibli Shumayyil, Ya‘qub Sarruf, Farah Antun, Nicola Haddad, Salama Musa, Wali al-Din Yakan, Louis Awad, and others—have called for secularism in its Western sense: the separation of religion from the state, and the idea that religion is for God and the nation is for all. What is noteworthy is that they were all Christians, the majority of them Levantine Christians, whose civilizational allegiance was to the West. They did not belong to Islam, either as a religion or a civilization, and were educated in foreign schools and missionary institutions. Therefore, in their sincere call for progress and national advancement, it was easiest for them to adopt the Western model they knew and advocated—a model they saw embodied in the West’s tangible progress.” (Hanafi, “Secularism and Islam,” in the book Hanafi and al-Jabiri: Dialogue Between East and West, pp. 35–36)

We agree with Hassan Hanafi on the Christian roots of Arab secularism, and on the fact that some of the early leading theorists of Arab secularism in the early 20th century were Levantine Christians—and that some of the most prominent secularist thinkers today remain Levantine Christians. These Christian intellectuals, however, have failed to grasp a fundamental aspect of Islam: that Islam is both a religious and civilizational system at once, and it is inaccurate to describe the Islamic political system or Islamic law as being purely religious or purely secular. These Christian-rooted terms are inadequate to understand Islamic sharia, and they lead to distorted caricatures—such as George Tarabichi’s statement about the “spiritual Meccan Islam” versus the “temporal civil Medinan Islam.” (Tarabichi, Heresies, p. 22) In reality, Islam in both its Meccan and Medinan phases was filled with spirituality and practical politics simultaneously. It is sufficient to note that the core value of Islamic political thought—the principle of shura (consultation)—was first mentioned in the Meccan chapter of al-Shura, and then later in the Medinan chapter of Al-Imran.

However, we do not agree with Hassan Hanafi in his generalization: the Arab secularist movement was not exclusively a Christian phenomenon. Among its advocates—even in its most extreme forms—there were always both Arab Christians and Arab Muslims. Likewise, we disagree with Hanafi’s claim that these Christian Arab intellectuals had no affiliation with Islamic civilization. In fact, some of them do belong to Islamic civilization in its cultural sense. It is enough to point out that a significant number of Levantine Christian poets—beginning with Shibli Shumayyil, who heads Hanafi’s list—praised the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) in their poetry, despite not being Muslims themselves. The Syrian researcher Ghada Ghazal compiled these poets and collected their prophetic praise poetry in her master’s thesis, titled: “Prophetic Praise in the Poetry of Contemporary Arab Christian Poets.” I had the honor of supervising her work at the College of Islamic Studies at Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Qatar.

However, secularism remains a Christian—not Islamic—concept, regardless of whether its advocates are Christians or Muslims. The Muslim secularists in the Arab world—who oppose the political message of Islam and its role in public affairs and legislation—have internalized this Christian perspective as part of the broader Western cultural framework they have absorbed. Given the Christian roots of Arab secularism—whether it was preached by Christians or theorized by Muslims who subconsciously adopt a Christian lens—the well-meaning translator of The Impossible State need not have remarked: “The reader might be surprised to learn that Wael Beshara Hallaq was born in Nazareth, the city of Christ in occupied Palestine, in 1955, to a Christian family.” (The Impossible State, p. 13).

So what is so surprising about a Christian intellectual theorizing secularism in the Islamic world? What is truly surprising, in fact, is the level of naivety with which some Muslim intellectuals received Hallaq’s theories—to the extent that they considered him a savior of Islam from modernity and from the assaults of Orientalists—without realizing the deeper message Hallaq is attempting to convey beneath the dust of his battle with Orientalism or modernity. That message ultimately imposes a Christian perspective on Islamic culture, one that contradicts the very essence and spirit of Islam! When a Christian intellectual—whether Western or Arab—advocates secularism, he is returning to his roots and living in harmony with his conscience and the spirit of his religion, because secularism is fully consistent with the spirit of Christianity. As Hassan Hanafi rightly observed: “What took place in the modern era—the separation between spiritual and temporal authority—is in fact a return to the spirit of early Christianity.” (Hanafi, Dialogue between the East and the West, p. 34). In contrast, when a Muslim intellectual theorizes secularism, he experiences alienation from his own self and a condescending superiority towards his people, their conscience, and their faith, ultimately guiding his society toward despotism, fragmentation, and civil wars.

Fourth: Comparative Religion and the “Christianization of Islam”

In the context of pursuing what Abu Ya‘rub al-Marzouqi called the “Christianization of Islam”—that is, coloring it with a Christian worldview—Arab secularists tend to promote the passive and mystical aspects of Muslim history and current reality. The philosopher-poet Muhammad Iqbal was among the earliest modern thinkers to criticize this stagnant spirit that some attempt to associate with Islam, distancing it from the method of the Prophet ﷺ and his Companions. Abu al-Hasan al-Nadwi recounted a delightful encounter with Iqbal, saying: “The conversation turned to the presence of some Sufis and their ecstasy during sama’ (listening to spiritual music). Iqbal commented: ‘The Companions were overtaken by joy, emotion, and chivalrous enthusiasm while mounted on their horses in the battlefield of jihad.’” (Nadwi, The Glory of Iqbal, p. 7)

Several centuries before Iqbal, the political jurist of Granada, Ibn al-Azraq, observed the political distinction between the Islamic faith and other religions. He noted that matters of governance and authority are foundational and intrinsic to the structural makeup of Islam from the very beginning. This is unlike other religions, where interest in political affairs was a later and incidental development in their historical trajectories, not a constitutive element of their original framework. Politics, he argued, is an essential core of the Islamic tradition: “It is not so with other religions… for its [political element’s] presence in them is merely incidental.” (Ibn al-Azraq, Bada’iʿ al-Silk fī Ṭabā’iʿ al-Mulk, p. 97)

What Ibn al-Azraq mentioned applies most accurately to Buddhism and Christianity, primarily. Islam, however, was not the first monotheistic religion to carry a political dimension. There were prophets among the Children of Israel before Islam whose missions explicitly included political and military aspects. This is confirmed by both the Qur’an and the Old Testament. Among these prophets are Moses, David, Solomon, and Joseph (peace be upon them all). Islam, therefore, is the heir to a long-standing tradition of blending prophethood and politics among the Semitic peoples. It is not an innovation in this regard. On the contrary, Christianity can be considered the anomaly—a deviation in this domain and an exception to the prophetic tradition of the Semitic religions, not the norm.

Ibn Taymiyyah was insightful in his comparison of Islam with Judaism and Christianity, as he clarified the comprehensive nature of Islam and its ability to encompass all aspects of life. He said: “Moses came [in his law] with justice, and Jesus came to complete it with grace, while the Prophet (peace be upon him) brought in his law both justice and grace.” (Ibn Taymiyyah, Al-Jawāb al-Ṣaḥīḥ liman Baddala Dīn al-Masīḥ, 2/23) It seems that Ibn Taymiyyah was here inspired by the Qur’anic verse: “Indeed, Allah commands justice and excellence [grace].” (Surah An-Nahl, verse 90)

This combination of justice and excellence (grace) in Islam entails the necessity of integrating both truth and power, and religion and state. The state is essential to transfer the practical rulings of Islam — those related to people’s rights — from the realm of moral commitment to the realm of legal enforcement. And religion is essential to the state, as it provides it with political legitimacy, making people’s obedience to authority stem from conviction rather than coercion.

Yet those pursuing the “Christianization of Islam” — like Wael Hallaq — are keen to promote a defanged version of Islam, one that does not stand with the oppressed, nor restrain the oppressor, and that fails to reflect the authentic message of Islam and its liberatory mission. Instead, it is a hybrid concoction drawn from heretical piety and counterfeit asceticism that seeped into Islamic culture from Christian and Buddhist monastic traditions. Wael Hallaq has taken it upon himself to pose as a theorist of Islam’s future and its contribution to the fate of humanity.

But the Christian spirit and Christian terminology ultimately betray him. When he says, for example, that “everything in the world is historical, including God Himself, in a certain sense” (The Impossible State, p. 63), or when he says, “in this equation, the poor are an essential part of God, and He is an essential part of them” (The Impossible State, p. 284), he is clearly internalizing a Christian theological perspective—with its doctrines of incarnation—as well as a Christian social ethos rooted in monasticism. All the while, he is celebrated by gullible Muslims as a defender of Islam and a champion of its cause.

Wael Hallaq has acknowledged that the secular experiment in the Islamic world was a miserable failure. He writes: “This project of secularization was tried and adopted during the first three quarters of the twentieth century. But there is overwhelming evidence of its significant failure, as reflected — among other things — in the collapse of Nasserism and socialism, and the subsequent rise of political Islam after the 1960s.” (The Impossible State, p. 47).

Yet Hallaq persists in promoting a Christianity-tinged form of secularism, employing the same circuitous and ambiguous methods he often uses when discussing Islam’s present and future. He reduces Islam’s universal mission and future potential to the mysticism of Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī from the classical era and the spiritual philosophy of Ṭāhā ʿAbd al-Raḥmān in the modern era. (On al-Ghazālī, see The Impossible State, pp. 235–248. As for Ṭāhā ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, while Hallaq does not devote extended discussion to him, he praises four of his works in footnote 295.)

What is striking is that both Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī and Ṭāhā ʿAbd al-Raḥmān lived during similarly turbulent moments, marked by internal fragmentation and external penetration into the heart of the Islamic world — by hostile powers with Christian backgrounds (the Crusaders during al-Ghazālī’s era, and Europeans, Americans, and Russians in Ṭāhā ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s time). Yet both figures withdrew from the struggle that the Qur’an mandates and that moral duty demands, becoming absorbed instead in their own intellectual worlds and spiritual abstractions — as if the Ummah, being slaughtered from vein to vein by its enemies, was of no concern to them.

The Crusaders stormed Jerusalem and massacred its inhabitants, sparing only a small remnant, some of whom fled to Damascus — while Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī remained in seclusion, immersed in his contemplations in a corner of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. As Muslim outrage erupted across Greater Syria, Iraq, and beyond, the Damascene scholar ʿAlī ibn Ṭāhir al-Sulamī authored a treatise on the virtues of jihad to rouse the spirits of the people and laid out a political and military vision for revival. Pain and grief coursed through the body of the Islamic world everywhere… all the while, al-Ghazālī remained secluded, as though nothing were amiss. And when he finally emerged from his isolation and returned to his hometown in the heart of Persia, he never once acknowledged what had taken place, never spoke of the Crusades or the obligation of jihad — until the day he died.

It is to Ibn Ṭāhir, al-Harawī, and others of conscience who bore the burden of the ummah, that credit must be given for the emergence of the generation of Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn, not to al-Ghazālī and those like him who withdrew from public life. Perhaps the contemporary Azhar scholar Muḥammad Yūsuf Mūsā was not mistaken when he described al-Ghazālī’s ethical vision in his book Philosophy of Ethics in Islam, stating:

“Al-Ghazālī, as he was writing about his ethical doctrine, was not concerned with the public good… His doctrine is not one upon which society can be built, nor one that leads to the well-being of the ummah. The happiest days for Western nations — who fight wars to colonize the East — and for the enemies of Islam lying in wait to strike, would be the day they find Muslims adhering (God forbid) to the doctrine of al-Ghazālī: adopting his goals as their own and following his method as their guide. For then they would be reduced to nothing, or to the likeness of nothingness, in this life that shows no mercy to the weak.” A life that reminds us of the poet’s words:

“Wolves prey on those without dogs,

But fear the charge of a lion on the prowl.”

What Muḥammad Yūsuf Mūsā said about al-Ghazālī could equally apply today to Ṭāhā ʿAbd al-Raḥmān. He is immersed in theorizing a contemporary doctrine of political Sufism — one that flees from reality rather than confronting it. He overlooks the inherently conflictual nature of politics, indulges in obscure terminology, and engages in theoretical luxury that ultimately leads to legitimizing the status quo. The fundamental flaw in Ṭāhā ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s political theory is his neglect of the principle of counteraction (mudāfaʿah), which — according to the Qur’ān — is what protects society from corruption: “Were it not that Allah repels some people by means of others, the earth would have been corrupted.” (Sūrat al-Baqarah, 2:251)

Instead of this, he constructs a strange alternative principle, which he calls “spiritual disruption” (al-izʿāj al-rūḥī). He dreams that this disruption can change the political reality, but only through non-confrontational means — steering clear of military resistance, which he refers to as “chaotic action”, and equally distant from civil resistance, which he describes as “electoral action” (cf. Rūḥ al-Dīn, p. 309). His model relies instead on a form of pleading that eventually amounts to begging, since, as he says: “disruption is a form of emotional pleading.” (Ṭāhā ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, Rūḥ al-Dīn, p. 289)

Ṭāhā ʿAbd al-Raḥmān adopts a stance of neutrality in the ongoing struggle between oppressive rulers who hold dominion over their peoples and the opposition movements striving to liberate them. He regards both sides as equally driven by the desire for domination and rule through coercion — a posture of complete moral passivity, though paradoxically, in the name of morality! It is as if he fails to recognize that the aim of revolutions is to liberate people, not to rule over them — and this is the fundamental distinction between a revolution and a coup. Both the Qur’an and history testify that politics is about taking principled stances and resisting injustice, not about delivering sermons or placing hopes in the conscience of a tyrant. And there is no doubt that people, by their innate humanity and Islamic instinct, have understood this reality — which is why they took to the streets crying out: “The people want…”, not with supplication, and certainly not with begging.

To be fair, neither Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī nor Ṭāhā ʿAbd al-Raḥmān lacks intelligence or insight — both are among the most brilliant minds and thinkers in the Islamic tradition, and both are men who love God and His Messenger. The real problem lies in their entrenchment within a distorted religious culture, severed from the Qur’anic source and the Prophetic method — a culture of mystical passivity and lethargy inherited from Christian monasticism and Buddhist asceticism. So, was it a mere coincidence that Wael Hallaq chose al-Ghazālī from the classical tradition, and Ṭāhā ʿAbd al-Raḥmān from the modern era, as his models for the ethical vision of Islam he promotes? Or is this simply part of the broader “intellectual struggle in colonized countries”, to borrow the title of Malek Bennabi’s book?

Hallaq and his admirers — and the admirers of his admirers — may well accuse their critics of sectarianism and fanaticism. Indeed, Hallaq himself accused the distinguished Egyptian-American scholar Mohammad Fadel, Professor of Islamic Law at the University of Toronto, of having a “narrow-minded, bigoted, and short-sighted view” (The Impossible State, p. 23), merely because Dr. Fadel, with the brilliance of a well-grounded scholar, pointed out the methodological flaws and scholarly errors in Hallaq’s book Shari‘a: Theory, Practice, Transformations — all while maintaining exceptional courtesy and offering generous praise of Hallaq. But resorting to accusations changes nothing about the reality: that Wael Hallaq is part of a sustained effort to tame Islam, to transform it into a de-fanged religion, infused with a Christian or Buddhist ethos — one that neither supports the oppressed nor restrains the oppressor.

Whatever the case may be, the Muslim conscience will continue to see the true essence of Islam as vibrant and alive in the Qur’an, and in the life of the Prophet ﷺ and his Companions — those who were thrilled to ride their steeds into the battlefield of jihad — not in the life of some dervish lost in silence, contemplation, and dreams, nor in the posturing of some coward hiding behind philosophy and clever rhetoric.

Fifth: The Impossible State — Between Western Critique and Arab Hype

The Arabic translation of Wael Hallaq’s book The Impossible State was accompanied by a wave of intense promotion. I had the opportunity to read dozens of reviews of the book, both in Arabic and English. I found that many of the English-language reviews were critical of the book, exposing weaknesses in its evidentiary support and logical structure. In contrast, the majority of the Arabic-language reviews tended to be uncritical hype, both for the book and its author. One reason for this is that most of the Arabic reviewers had not engaged with the broader corpus of Hallaq’s jurisprudential and intellectual output—which would have helped them place The Impossible State in its proper context. Instead, some younger readers became preoccupied with polemics and argumentation, rather than careful reading and critical analysis.

Thanks to this intense promotion—driven more by the ideological struggle against Islamic political movements than by genuine scholarly concerns—Wael Hallaq attained a status unprecedented for a non-Muslim scholar in the field of Islamic jurisprudence. Despite the clear evidence in his academic work that he is an orientalist who adopts the religious and historical biases typical of Orientalist thought, he has come to be seen—at least in the eyes of some naïve young Muslims—as a defender of Islam against Orientalist critiques, and even as a theorist of Islamic ethics!

Hallaq is keen to present himself to the Arab audience in the second role, not the first—that is, as a defender of Islam against Orientalism, not as an Orientalist. In a special preface to the Arabic translation of his book The Origins and Evolution of Islamic Law, Hallaq admonishes Muslims that they do not need to “feed off the leftovers of others” (p. 15). He also claims that the aim of the book is to “undermine the Orientalist discourse” (p. 10) and is “an attempt to rectify this Orientalist discourse and its global rhetorical authority” (p. 15). Two things caught my attention, both rather amusing: the first points to Hallaq’s success in marketing himself, and the second highlights a strange irony embedded in that self-promotion.

The first point is that the editors of the annual publication The 500 Most Influential Muslims in the World—published in English by both the Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding in Washington and the Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre in Jordan—included Wael Hallaq among these five hundred influential Muslim figures for the year 2009, alongside a number of Muslim heads of state, Islamic scholars, preachers, and religious guides! The editors of the report did not even bother to ask themselves what religion Hallaq actually adheres to, before including him in a book specifically about individuals whose influence stems either from their implementation of Islam or from being Muslim, as stated in the book’s introduction.

The second point is that Hallaq refers to Emile Tyan (1901–1977) and describes him as “the well-known Lebanese Orientalist” (see The Impossible State, p. 126), while he does not consider himself an Orientalist! The irony here is this: what makes a Lebanese Christian who specializes in Islamic law an Orientalist, but exempts a Palestinian Christian who also specializes in Islamic law from this label—despite the fact that both men were born and raised in the Levant, pursued their undergraduate studies there, and then moved to the West to complete their education and integrate into Western academic life? The truth is that Wael Hallaq is an Orientalist through and through, not merely because he is a non-Muslim academic specializing in Islam—which, in itself, is not objectionable—but because he adopts both the explicit and implicit orientalist assumptions that cast doubt on the authenticity of the Islamic message and the morality of the Prophet (peace be upon him), despite all his conflicts with other Orientalists, he (Wael Hallaq) has managed to claim a prominent position in the field of Islamic studies in the West.

The most important Orientalist assumption that these scholars adopt regarding the authenticity of the Islamic message is the claim that Islam is merely a false imitation of Judaism and Christianity, shaped by reactive motivations and a constant effort to assert itself in contrast to those two religions. Hallaq has fully adopted this Judeo-Christian-oriented Orientalist perspective, as is evident, for example, in his statement: “Before arriving in Medina, Muhammad (peace be upon him) was not thinking of forming a new nation, nor of launching a new law or legal system… But a new reality imposed itself upon him when he found himself face to face with the Jews in Medina… And when the Prophet’s hopes in them failed, he began to distance himself from those rituals that the new religion had shared with Judaism.” (Wael Hallaq, The Origins and Evolution of Islamic Law, p. 46)

This doubt cast on the authenticity of the Islamic message is repeated in several of Hallaq’s books. Among his statements is the following: “And from the Qur’an, we learn that at a certain point after his arrival in Medina, Muhammad (peace be upon him) began to think of his message as one that carries God’s law, just like the Torah and the Bible.” (Wael Hallaq, A History of Islamic Legal Theories, p. 21) He also claims that after the Prophet’s migration to Medina: “He began to conceive of his religion as one that must provide the Muslim community with a body of laws distinct from those of other religions.” (Wael Hallaq, A History of Islamic Legal Theories, p. 23)

As for Wael Hallaq’s adoption of the Orientalist slanders against the character and moral integrity of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, one example will suffice—an accusation often repeated by Orientalists: namely, that the Prophet ﷺ “exploited” minor disputes with the Jews of Medina as a pretext to expel or kill them. What an ugly accusation—one that implies that the Messenger of God ﷺ was treacherous and broke covenants, when in fact he was the most faithful in keeping promises and the most trustworthy in fulfilling obligations. Hallaq, regurgitating the falsehoods of Orientalists, says: “More importantly, the Jews represented an epistemic threat to Muhammad, for their doubts regarding his message were bolstered by their status as the guardians and interpreters of monotheism and sacred monotheistic texts. A partial solution to this threat was realized early on, when Muhammad exploited a conflict between the Jewish tribe of Banu Qaynuqa‘ and some Bedouin Arabs of Medina. He moved against Banu Qaynuqa‘, besieged the tribe, and forced them to leave the town, taking their wealth with them. In doing so, he reduced the threat and strengthened his position in Medina.” (Wael Hallaq, The Origins and Evolution of Islamic Law, p. 20 of the original English edition)

I have preferred to quote this passage directly from the original English text, because the Arabic translator of the book, Riyadh Al-Milady, rendered the paragraph inaccurately and unfaithfully in several places (see page 46 of the Arabic translation). The translator altered the meaning in three distinct ways:

- The phrase “The Jews represented an epistemic threat to Muhammad” was completely reversed in meaning by the translator, who rendered it as:

“The Jews found in the Prophet an epistemic threat to themselves!” - The translator avoided using the word “exploited” (exploiting), which Hallaq clearly used in the original English. Instead, he replaced it with a softer word, rendering it as: “benefited from” (أفاد).

- The translator also added the invocation of peace and blessings upon the Prophet ﷺ, which is common practice in Arabic translations of Wael Hallaq’s books.

And while it may be acceptable to consider the insertion of the salutation upon the Prophet ﷺ a commendable gesture out of respect for the sensitivities of Muslim readers, the first and second alterations in the paragraph constitute deliberate deception by the translator, aiming to mislead Muslim readers and distort Hallaq’s original words—which the translator clearly understood would be shocking to Islamic beliefs. Hallaq himself may also be complicit in this deception, if the translation was carried out under his supervision, endorsed by him, or reviewed by him prior to publication, especially considering that he wrote a special preface for the Arabic edition. In any case, the translator’s conduct here demonstrates the urgent need for Muslim readers to consult Hallaq’s original English texts directly, rather than rely on translators more concerned with marketing Wael Hallaq than with scholarly integrity.

Despite Wael Hallaq’s adoption of the religious and historical assumptions of Jewish and Christian Orientalists—assumptions that undermine the authenticity of the Islamic message and the moral integrity of the Prophet ﷺ—he still echoes praise for the Islamic legal and political tradition. This serves as a manipulation of traditionalist sentiment, and a stirring of folkloric pride in the past—the very trap that Edward Said, with his sharp intellect and intellectual honesty, warned against. For instance, Hallaq praises models of “Islamic dynastic governance,” saying: “Legislative authority in modern liberal democracy possesses fewer powers by comparison.” (The Impossible State, p. 13) This statement can only be read in one of two ways: as an act of innocent naïveté on Hallaq’s part, or as a deliberate attempt to sedate Muslims with ill intent. We, however, lean towards assuming ill intent here for Hallaq, so as not to attribute it to naivety, as he is far from it!

In response to the Orientalist notion of the “Eastern despotism,” Hallaq wrote: “In light of the constitutional organization of Islam, the Islamic worldview honors society as the cradle of life and the space of meaningful living, and considers despotism—along with its political source in sultanic power—far less harmful than its European counterpart.” (The Impossible State, p. 135). Yet this rebuttal of the charge of Eastern despotism seems more like a confirmation of it, attributing it instead to the Islamic worldview! While many Western thinkers trace despotism back to Chinese, Indian, or Persian traditions, Hallaq here implicitly associates it with Islam itself. This type of “rebuttal” that amounts to reaffirming the accusation is common in Hallaq’s writings, which are characterized by a twisted logic whenever Islam and politics intersect. More often than not, Hallaq takes every noble feature in the history of the Shari‘ah and weaponizes it against the possibility of constructing any modern state based on Shari‘ah.

Among the dishonest praises Hallaq offers of Islamic political history is his claim: “The ruler, like any other subject of the Sharia, remained subject to any civil litigation… Likewise, he could be punished for any violation of criminal law or Qur’anic hudud.” (The Impossible State, p. 140). This is an idealized, fantastical image that is far from historical reality. If this were true, then how many rulers in Islamic history were flogged for drinking wine—one of the most common hudud violations in royal courts of the past? How many rulers were executed in retaliation (qisas) for unjustly killing one of their subjects—though many did so throughout Muslim history? It is as if Hallaq—when speaking of equality before the law between ruler and subject in Islamic history—never heard of the authority of “whim and desire” that Ibn Khaldun so astutely dissected in his Muqaddimah! And this is not the only example of Wael Hallaq’s ignorance of Islamic political heritage.

It does not serve the future of Muslims to build it upon a fantastical vision of the past, or to boast about things that never were. In fact, this game of glorifying the past to kill the future may well be part of Hallaq’s strategy of “persuasive effectiveness.” We already cited earlier in this essay his own words: “One of the essential conditions for the persuasive effectiveness of any discourse is that the motives behind the discourse not be clear to the reader or listener.”

(*Wael Hallaq, The Origins and Evolution of Islamic Law, p. 13).

Malik Bennabi’s Perspective on Orientalism

Nearly half a century before the publication of The Impossible State, the philosopher of Islamic civilization Malik Bennabi delivered a lecture titled: “The Production of Orientalists and Its Impact on Modern Islamic Thought.” This lecture was later published as a booklet under the same title. In this work, Bennabi offers profound insights that may help in understanding the phenomenon of Wael Hallaq within the broader history and context of Orientalism. He distinguishes between two types of Orientalists:

- The first are those hostile to Islamic history, characterized by all kinds of criticism and disparagement.

- The second are those who praise Islam’s past, yet surround its future with doubt and ambiguity.

(The Production of Orientalists, p. 24)

What is particularly striking is that Malik Bennabi, with his keen insight, found that the second type of Orientalists may be no less dangerous to the Muslim conscience than the first type—and may even be more dangerous in certain circumstances. The hostile Orientalists, who attacked the Islamic heritage, left little trace on contemporary Islamic culture, because the alert defenses of the Muslim conscience quickly repelled their claims, exposing their flaws and often blatant bias. As Bennabi puts it: “Their output—assuming it did affect our culture to some extent—did not significantly stir or direct our overall body of ideas, because we had within us a natural readiness to confront its influence instinctively, a confrontation in which the innate factors of cultural self-defense intervened.” (The Production of Orientalists, p. 6)

As for the Orientalists who praise the Islamic heritage, it is very easy for them—amid their praise—to pass on all their doctrinal biases against Islam without encountering any defense from the Muslim mind, because today that mind is crisis-ridden, suffering from an inferiority complex and “seeking a dose of pride to overcome the humiliation inflicted upon it by the victorious Western culture, just as an addict seeks a dose of a drug to temporarily satisfy their pathological need” (Production of Orientalists, pp. 11–12). These praising Orientalists have provided that drug for Muslims in the form of flattering commendations, which the troubled Muslim mind uses to justify its own weakened, shaken self-confidence, while forgetting to strive for the present and the future. In this regard, Bennabi says: “We find in these praising Orientalists a tangible effect that we can conceive of, insofar as we realize that there was no readiness in our souls to react, since from the outset there was no justification for a defense that had lost its usefulness; it was as if its apparatus became disabled for this very reason in our souls.” (Production of Orientalists, p. 7)

Malik Bennabi compares the flattery of some Orientalists toward the Muslim heritage—while they simultaneously undermine the authenticity of the Islamic message, seek to destroy Islam’s future, and strip the contemporary Muslim of spiritual dignity—to someone who consoles a hungry poor man by telling him stories of his ancestors’ wealth. The poor man fills his ailing self with pride while he sleeps on the ground, content to remain in his lowly state: “When we speak to a poor person—who cannot find enough to satisfy his immediate hunger—about the vast wealth that his fathers and ancestors once possessed, we only provide him with a temporary amusement, like a kind of narcotic that momentarily isolates his mind and conscience from feeling the pain. We certainly do not cure it. Likewise, we do not cure the illnesses of a society by recalling the glories of its past.” (Production of Orientalists, p. 13)

Malik Bennabi did not fail to point out the Orientalists’ awareness of the complex of pride in the past within Muslim culture today, and how some Muslims seek refuge in the memory of a distant past to avoid confronting the present reality and the coming future. Malik noted the “sensitivity of Muslim masses to the glories of their past” and, with insightful vision, warned of “the possibility of exploiting this sensitivity to divert those masses from their present.” This aspect is particularly important because it coincides with the peak of the overwhelming wave sweeping the world today in the form of intellectual conflict. (Production of Orientalists, p. 17)

Malik Bennabi concludes in his valuable reflections that “Orientalist production, in both its types, has been harmful to Islamic society… whether in the form of praise and flattery that diverted our contemplation from our present reality and immersed us in the illusory bliss found in our past, or in the form of refutation and belittlement that turned us into defenders of oppression over a collapsing society… whereas it is our duty to confront it insightfully, of course, but relentlessly, taking into account only the Islamic truth that does not yield to any circumstance in history, without surrendering to others the right to impose their noise and defend it out of their own vested interests.” (Production of Orientalists, p. 25)

The work of Orientalists, both the flattering and the disparaging, is a means of “shattering consciences and minds” (Production of Orientalists, p. 24), filling a void in a culture that has lost its historical initiative and accepted being cornered. “Any ideological vacuum not occupied by our ideas awaits ideas that are contrary and hostile to us. This is the general rule, and specialists in intellectual struggle know it as well as they know their own children.” (Production of Orientalists, p. 45)

Sometimes the filling of the void comes in the form of blatant attacks that exhaust the Muslim mind in defense, and other times in the form of a narcotizing praise that drowns the Muslim mind in a glorious past, distracting it from the bitter reality and the bleak future. This latter form is the most dangerous because of its twisting nature: “The intellectual struggle has its own logic, generally a twisted line, requiring transition from one stage to another, through intermediate stages that impose bends and twists on the path.” (pp. 45-46).

Wael Hallaq belongs to the category of Orientalists who praise the history of Islam, yet “surround its future with suspicion and ambiguity,” in the words of Malik Bennabi, while also attacking the authenticity of the Islamic message itself. Will the naive young Muslims understand this, or will they surrender to intellectual laziness and cling to illusions?!

Sixth: Coercive Secularism and the Erosion of the Chains of Dependency

Secularism in the West was born as a voluntary phenomenon, concurrent with the rise of democracy and political freedom, and in societies already detached from their religion. In contrast, secular ideology in the Islamic world was born as a coercive phenomenon—imposed at the tip of the colonial state’s spears, and later by its offspring: the authoritarian state. It became a tool to forcibly strip religious societies of their faith. Turkish researcher Ahmet Kuru noted—through his comparison between French and Turkish secularism, both of which are “hard” forms of secularism—the difference in historical trajectories between Kemalist Turkey and the French Third Republic, which lasted for seven decades (1870–1940).

In France, the devout French Catholics allied themselves with the old regime and the counter-revolution, and sought to use instruments of coercion—including the army—to maintain the decaying authoritarian order. They fought against the revolutionary forces, which were backed by popular support. In contrast, in Turkey, the religious political forces were the fuel of the struggle for democracy over the past decades. Meanwhile, the Turkish secularists relied on coercive means—especially the military—to control the people and prevent democratic reform and change.

Ahmet Kuru writes: “In the early days of the French Third Republic, the Catholics planned to contain the influence of the republicans in parliament by ensuring monarchist control over the presidency and the military… In contrast, in the Turkish case, the adherents of assertive secularism attempted to limit the powers of the elected parliament through Kemalist dominance over the presidency, the military, and the judiciary.” (Ahmet Kuru, Secularism and State Policies Toward Religion: The United States, France, and Turkey, pp. 369–370.)

This historical divergence led to a divergence in the present, due to the difference between the French Christian society and the Turkish Muslim society in terms of religious and cultural background. French secularism retained its democratic and liberal character and was accepted willingly by the majority of French society, which helped foster social unity and cohesion. In contrast, Turkish secularism took a coercive and authoritarian turn due to the society’s resistance to it, resulting in a deep rupture within Turkish social identity.

The Turkish researcher observed this and wrote: “In the present time, the low religiosity of French society corresponds with the strict secular ideology of the state. It is possible that both are comfortable with the absence of religion from the public sphere. Turkey suffers from a contradiction, in that its society is among the most religious, while its state policies are among the most extreme in terms of strict secularism.” (Ahmet Kuru, Secularism, p. 373)

The struggle that Turkey is experiencing today closely resembles — to a large extent — the conflict within France during the era of the Third Republic, where forces of tyranny and backwardness clashed with forces of freedom and renewal. The essential difference is that, in the French case, the devout Catholic French sided with the forces of tyranny and backwardness, while the French secularists aligned themselves with freedom and progress. In contrast, in contemporary Republican Turkey, it is the Turkish secularists who stand with tyranny and backwardness, while Islamic forces are at the forefront of defending freedom, renewal, prosperity, and independent decision-making.

Indeed, what the Turkish secularists adopted in terms of coercion and repression is exactly what many Arab secularists have mirrored. Most of them sided with authoritarian regimes, forming alliances with military institutions to crush popular revolutions. They even supported blatant military coups against democratically elected Islamic governments — as witnessed in Algeria two decades ago, and more recently in Egypt in 2013. In Tunisia, secularist forces nearly derailed the revolution by attempting to oust the Ennahda Movement from power, despite its victory in fair and transparent elections. One of the striking ironies was hearing, just before Sisi’s coup in 2013, some Arab thinkers — who constantly portray themselves as “democratic intellectuals” — advocating for the military’s control over the political process in Egypt. This stark contradiction reveals how certain secular elites in the Arab world have often preferred authoritarian stability over democratic outcomes, particularly when those outcomes favor Islamic political movements.

Coercive secularism in the Arab and Islamic world did not only lead to a fragmentation of cultural identity, but it also served as a wide gateway through which political and strategic dependency entered. Samuel Huntington observed the link between secularism and dependency in the Turkish case. He explained that the greatest barrier preventing Turkey from transforming into a “core state” leading the Islamic world is the excessive ideological secularism imposed on its people, which resulted in dependency on the West—despite Turkey’s position, history, and culture calling for it to be a leader in the Islamic world, not a follower of the West.

Samuel Huntington observed that the constraints of secularism and dependency imposed on Turkey have begun to erode. This erosion is largely due to the Islamic awakening in Turkey and the increasing presence of Islam in Turkish public life in recent decades. Democracy in Turkey, as Huntington accurately noted, led to a “return to roots and to religion” (The Clash of Civilizations, p. 241). As a result, “the Islamic resurgence has changed the character of Turkish politics” (The Clash of Civilizations, p. 241).

In his book published eighteen years ago, Huntington predicted that Turkey would eventually free itself entirely from the artificial constraints of secularism and dependency imposed upon it, once it fully rediscovers and redefines its identity. He wrote: “What if Turkey redefined itself? At some point, Turkey might be ready to abandon its frustrating and humiliating role as a supplicant begging for membership in the Western club, and resume its more influential and noble historical role as a principal interlocutor on behalf of Islam and a rival to the West.” (The Clash of Civilizations, p. 291). This is precisely what has begun to happen over the past fifteen years during which Islamic political forces have governed Turkey. While the path is still in its early stages, it clearly signals a historical trajectory in which Turkey is reclaiming its Islamic authenticity, its self-confidence, and its global stature.

And the more Turkey frees itself from the internal oppression once exercised by the deep state, and from the dependency imposed on it by the West, the faster and more firmly it will proceed in this direction. The recent statement by the Speaker of the Turkish Parliament about the possibility of removing secularism from the Turkish constitution in the future, along with President Erdoğan’s recent interview with Al Jazeera, in which he interpreted the secularism mentioned in the constitution in an Islamic framework — these are all signals of Turkey’s direction in the coming era. Turkish secularism has been defeated by democracy, because in Turkey, the people are the wali al-amr (the legitimate authority), and the ruler listens to and obeys them. In contrast, in the Arab world, the ruler stands apart from the nation and accuses it of being nothing more than a rebellious faction of khawarij! Despotism and secularism have been — and still are — allies in the Arab world.

The Arabs are not in need of treading the winding paths that Turkey has followed, nor of enduring the pains it suffered before beginning to return to its true self and reclaim its Islamic identity. The Arab peoples have never been defeated in the battle over identity, nor have they ever truly abandoned their Islamic identity—despite all the calamities they endured at the hands of their despotic rulers, especially those ideologically driven ones among the socialist nationalists who resorted to coercive social engineering to strip Arab societies of their Islamic beliefs. What the Arabs need today is to activate the political values of Islam that still remain—and will continue to remain—deeply rooted in their culture.

And when the Arab Spring began, the Islamists were the greatest force lifting the Arab revolutions against tyranny, while the secularists were the strongest support for the counter-revolutions. The counter-revolution and its international backers did not target the democratic Islamic forces arbitrarily—they did so with full awareness that these Islamic forces were the backbone and the moral and social incubator of the uprisings against oppression and authoritarianism. It was a striking irony to witness Arab secularists in recent years calling for the establishment of “civil” democratic states, while they simultaneously supported fascist military regimes like those of Sisi and Assad. This has led us to the dramatic scene we are living today—where the Islamists lose more of their martyrs’ blood each day, while the secularists lose more of their dignity.

Mature political forces focus more on the rule of law than on the source of the law. What matters to them is how the country is governed, more than who governs it. The true measure of a political group’s commitment to democracy lies in its willingness to accept electoral defeat—and in this test, the Arab secularists have failed miserably. The gravest logical and moral contradiction committed by Arab secularists has been their call for democracy while rejecting its results. The reason behind this contradiction is their persistent view of Islamists as second-class citizens, and of the people as minors under guardianship. The most democratic among Arab secularists is the one who tolerates Islamists’ presence in the public sphere—as subjects, not as rulers. As for the least democratic among them, he seeks to uproot them by force.

Thus, political selfishness drove Arab secularists to insist on denying Islamists the right to govern—even if that meant depriving the entire population of its freedom. They hate the Islamists more than they love freedom. They defend minority rights while trampling on the rights of the majority. They reject the divine values of Islam without truly embracing the humanistic values of the West—leaving them “neither here nor there.” These contradictions in the positions and political culture of Arab secularists are a fundamental reason behind the faltering of the Arab Spring.

Politics is an integral part of Islam’s theological, ethical, and legal framework. The political values of Islam are rich and capable of inspiring Muslims—and indeed all of humanity—to build more just and noble political systems. In Islam, matters of governance and politics—despite involving temporal worldly interests—carry a devotional dimension that is only fulfilled when the state adheres to the authority of divine revelation. The issue of “referring matters to God and His Messenger”—in its foundational sense—is the key distinction between the Islamic system and the secular system today. It is the crux of the ongoing struggle between Islamic political forces, which seek to anchor the public sphere to Islamic authority, and secular political forces, which advocate for a human-derived authority cut off from divine guidance. By “secularists” here, I refer specifically to the minority among them who believe in human dignity and political justice. As for the majority of Arab secularists who support authoritarianism, they have no moral reference point at all—neither Islamic nor humanistic.

The problem with Arab secularists, it seems to me, lies in their failure to grasp what the brilliant Ibn Khaldun understood—that the political key to the Arab character is religion. He wrote: “Arabs do not attain sovereignty except through a religious coloring—whether prophecy, sainthood, or a profound religious influence in general.” (Muqaddimah of Ibn Khaldun, 189). Secularists see no path to Arab greatness except through erasing Islam from their hearts—as if they have forgotten that we are a people whom God has honored through Islam. They see no viable option for today’s Muslims other than a cultural and moral transformation that strips them of their identity, or else remaining trapped in the mire of backwardness and political oppression. This, in fact, is the essence of Wael Hallaq’s nihilistic vision and his impossible state, in which he concludes that Muslims must choose “either modernity without ethics, or ethics without modernity”—as aptly summarized by Abu Ya‘rub al-Marzouqi in his brief but incisive critique of Hallaq’s theory.

Ibn Khaldun’s triad of—natural rule (al-mulk al-ṭabīʿī), political rule (al-mulk al-siyāsī), and the caliphate (al-khilāfah)—may help clarify the position of Arab secularists who support authoritarianism on the scale of political values. Ibn Khaldun distinguished between three types of political systems: “Natural rule is the subjugation of the masses based on desire and personal whims. Political rule is the subjugation of the masses based on rational consideration of worldly benefits and the avoidance of harm. The caliphate is the subjugation of the masses based on the dictates of divine law (al-naẓar al-sharʿī) with respect to their interests in the hereafter and the worldly ones that are subordinate to them—for all worldly affairs, according to the Divine Law, are to be evaluated in light of their implications for the afterlife.” (Ibn Khaldun, Muqaddimah, 239)

The derivation of political values from Islamic texts is supported by Ibn Khaldun’s tripartite classification of governance. The highest form (highest-ranking) of political rule in Islam is the state of divine law and justice (Dawlat al-shar‘ wa al-‘adālah al-ilāhiyyah), which is founded upon mutual contract and consent in its establishment and is committed to both Islamic ethical and legislative authority. It combines consultative governance (shūrā) with Islamic reference (marja‘iyyah). This is the normative Islamic state, fully aligned with Islamic political values, as it adheres to the “dictates of divine law (naẓar shar‘ī)” and harmonizes “benefits related to the Hereafter and to this life,” as Ibn Khaldun expressed.

The middle-ranking political system from an Islamic perspective is the state of reason and human justice, which is not guided by divine revelation but strives to achieve justice and the public good based on the dictates of reason, experience, and human fairness. In the modern context, this definition applies to all democratic states that are founded on mutual consent and contractual agreement, but do not adhere to Islamic reference or authority. This type of system is aligned with Islamic political values in its structure and mechanisms, but not in its foundational reference.

The lowest-ranking political system from an Islamic perspective is the state of desire or whim, referred to by Ibn Khaldun as the rule of “desire and personal whims.” This is a state founded on coercion and compulsion, lacking commitment to any legal or moral reference, whether Islamic or otherwise. It includes all forms of tyranny and despotic regimes. Such a state of whim is in complete contradiction to Islamic political values—both in structure and function—even if the majority of its population happens to be Muslim.

It seems to me that Arab secularists today are faced with three options: either they wake up from their delusions and realize that Islam is the key to the Arab personality, and that a secular state based on consensus and choice is impossible in Arab societies, and thus renounce their secularist ideology and accept the “Shari‘ah state”—that is, a democratic state with an Islamic ethical and legislative reference. Or, they adopt some human spirit and fairness toward their opponents, and accept the “rational state”—a democratic state that accommodates both Islamists and secularists, without a predetermined Islamic or secular reference, but rather one decided by its people. Or, they persist in their delusion, as servants and courtiers in the entourage of despotism and the unjust “state of whims,” out of spite toward their political opponents from among the Islamists—until they are swept away by the fierce winds of change.

It is time for the Arab person to free themselves from the “modernity” of superficiality, adopted by secular elites detached from their social roots. The incident of (Bouazizi), which ignited the Arab Spring, exposed the fragility of this false modernity and its inherent contradictions. For the pseudo-modern secularism in Tunisia, which prides itself on having established equality between men and women, and opened up equal employment opportunities for women—including in the police force—failed to achieve even the minimum standard of true political modernity: namely, obligating the police to operate within the bounds of the law, restraining their oppressive hand, and preventing them from violating the dignity of the Tunisian citizen. Thus, the slap from a female police officer on Bouazizi’s face was the most telling expression of that contradiction. And Bouazizi’s self-immolation under the weight of wounded dignity was the illuminating spark that exposed that oppressive and false secularism prevailing in the Arab world.

Conclusion